By John A. Ostenburg

Occasionally, someone will come up with the idea that the housing cooperatives in Park Forest are not paying their fair share of property taxes. Let me tell you why that’s a fallacious argument.

First, a little background on what housing cooperatives are, how they came about in Park Forest, and why they are a definite asset to the municipality rather than a burden, regardless of how much they may produce in property taxes.

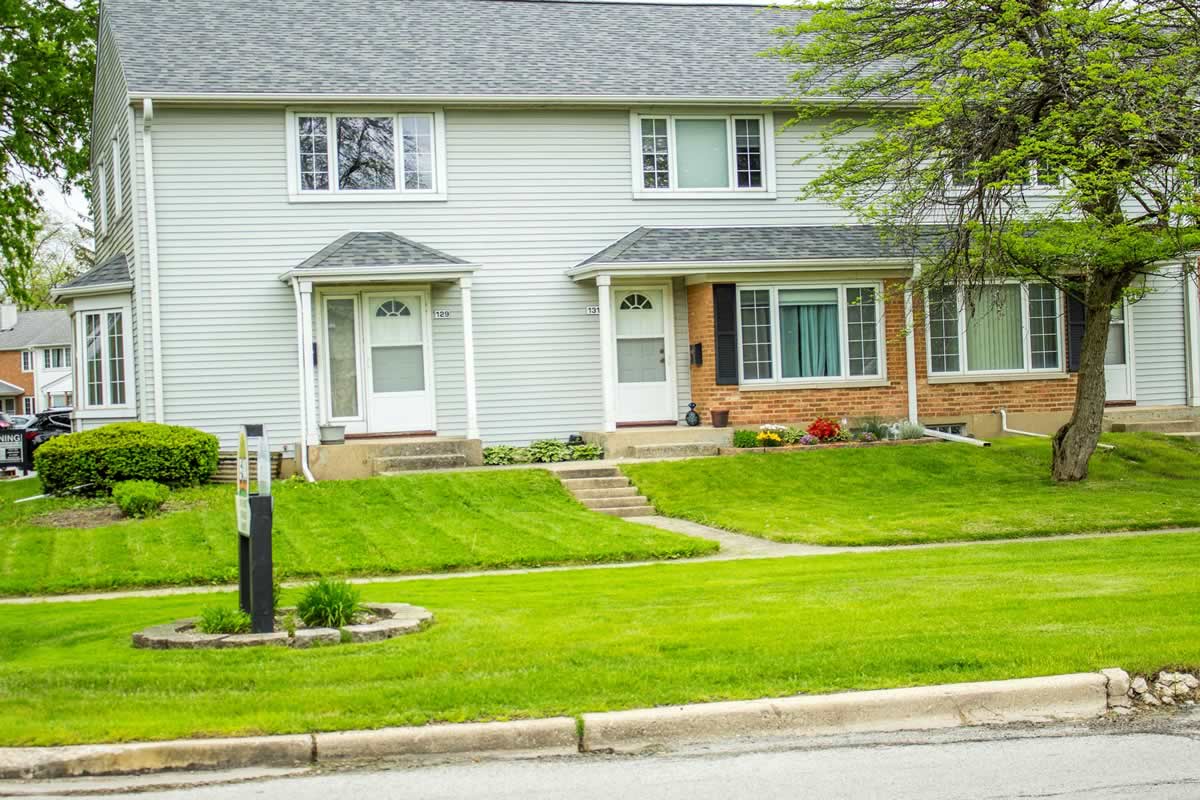

When developers Philip Klutznick, Nathan Manilow, and Carroll Sweet created housing in what today is Park Forest in the late 1940s, they intended it as a post-World War II housing opportunity primarily to accommodate returning GIs and others needing affordable housing. The first units were multifamily townhouses, some as row buildings and others as duplexes. The company owned by the developers – American Community Builders – served as the landlord for these units, all initially rentals. After completing the multi-family units, the developers began production of single-family residences. They placed all of those for sale to individual owners.

Welcome to the 60s

By the early 1960s, some renters in the multi-family area decided to purchase blocks of units as a group. They worked with the developers, and created a housing cooperative. Housing cooperatives are very popular in many regions of the United States. This is especially true in New York. Many of the renters had relocated from those regions and thus were familiar with the housing cooperative concept. It is a joint-ownership concept in which all the residents are stockholders in the corporation that owns the properties. The share of stock that the individual owns entitles him/her to reside in a specific unit. That stockholder pays a monthly carrying charge to the corporation. The carrying charge covers the expenses of maintenance of the properties and improvements. In a sense, shareholders thus rent their unit from the corporation they partially own.

Eventually, about two-thirds of the multi-family units of Park Forest became cooperatives. That led to five individual corporations. The bulk of the remainder stayed as rental units. A small number became condominiums. Within the housing cooperatives, the initial price for a share of stock was $200. Eventually, that share price changed to whatever the marketplace would allow. Today, for example, individual shares of stock may sell for as much as $25,000-30,000. They might sell as low as $2,000-5,000. This depends on what is happening within the larger housing market. It depends also on what types of amenities the individual unit associated with that share of stock may provide.

Improvements to Units Make a Difference

Regarding this latter point, some individual stockholders invested considerably in improving the units where they reside. Some have added decks. Others remodeled kitchens and bathrooms. Some put on additions or garages, etc. Residents of co-ops can only make these improvements with the approval of their Board of Directors of their cooperative corporation. Typically, carrying charges may increase if those amenities lead to more maintenance assistance for that improved unit. However, the stock price has never been comparable to what individuals pay to purchase single-family residences or condominiums. Instead, the stock share has always been more in the range of about one-fifth of what other residential property sales generate.

Figuring Out Property Taxes in Illinois

Property taxes in Illinois are based on the value of the properties from which the tax revenue is generated. Properties are assessed principally, therefore, on what the resale value of the property may be. This system alters slightly by various exemptions allowed for particular groups. These groups include older citizens, veterans, etc. Otherwise, the assessment is consistent with the resale value of the properties. This is why the amount cooperatives pay in property taxes per unit is lower than those of single-family homes or condominiums. This is true even though both applied tax rates are the same. The resale value of those other properties is, on average, about five times higher per unit than the resale value of cooperative properties. That leads to higher property taxes.

Some folks argue that the taxes should be based on the resale value of the complex as a whole. After all, that’s how the property taxes for rental complexes derive. However, to do that, the likelihood must exist that the property is sold as a whole. This is an extremely remote possibility – at best! The sale of a cooperative complex can only come with the decision of most shareholders. A majority must agree to sell their homes in one transaction.

Cooperatives are not Rentals

An owner of a rental complex, even joint owners, might well decide to sell the complex. Such a transaction would mean that few, if any, of those owners would actually lose their residences. They likely would see a profit in such a move. That possibility is not likely to occur with cooperative housing properties. There, the actual homes of all the sellers/residents would be lost in one transaction.

Owners of rental complexes may use the property as collateral for their benefit if seeking loans. They may do the same in other transactions where they need collateral. This speaks to the differences between rental complexes and cooperative complexes. As regards cooperative housing property, such an action only can occur to benefit the corporation as a whole. Individual shareholders do not have this advantage. Of course, some banks will allow an individual shareholder to use the value of an individual share of stock. But they base this on the same value as property taxes. Indeed, this latter course is how some shareholders finance the improvements they make to the units in which they reside.

Finally, we must recognize that large rental complexes differ from cooperative complexes. This is because the former are profit-producing entities, and the latter are not. Buyers of large complexes are willing to pay a specific price for the property. Why? They anticipate a profit on the subsequent rental of the individual units. The rental complexes, thus, are profit-generating businesses, not not-for-profit entities such as cooperatives.

The Value of Cooperatives Goes Beyond Taxes

Some years ago, Martin Ganzel told me a story. It underscores the value of the housing cooperatives to the overall condition of the Village. Mr. Ganzel was president of the former Bank of Park Forest. This bank is now US Bank in Park Forest. He said he spoke with a major banking official who drove through one of the cooperative neighborhoods. This official did not know that it was a cooperative. He commented to Marty his amazement. The multi-family buildings built in the late 1940s were as attractive and well-maintained as those he saw. Marty responded, “That’s because they’re housing cooperatives. Those folks make sure their properties are properly maintained.”

So let’s also consider how that condition, described by Mr. Ganzel, may be of value. What do the housing cooperatives offer to the municipality? What do they offer other local units of government? These contributions are every bit as beneficial as might be actual tax dollars.

No Subletting in Co-ops and Self-governance Matter

- Housing cooperatives do not allow subletting, meaning every shareholder is an actual resident. Many municipalities face considerable difficulties with absentee landlords. These renal owners fail to maintain their properties properly. This never occurs within a housing cooperative complex. Local government, therefore, does not have to pay court fees and other costs related to enforcement actions.

- Each housing corporation is self-governing. Each has its own Board of Directors and management. This assures that all residents follow various municipal codes. This relieves the local government of the costs of inspections and other code enforcement duties.

- The cooperatives each have a universal maintenance system. Therefore, many types of physical deterioration to residential structures existing in neighborhoods do not exist within these complexes. Because of this, many of our older citizens and single heads of households find housing cooperatives as ideal maintenance-free residences.

Improvements to Cooperatives

- Housing cooperatives often improve their complexes, relieving local government of the obligation to spend tax dollars. Some of these improvements may be in the form of shared costs for roadway or sidewalk improvements. Cooperative corporations may make some improvements, such as sewer-line corrections, at their own expense.

- Housing cooperatives have strict house and ground rules. These require that residents maintain specific public safety standards. Park Forest’s law enforcement officials respond to far fewer calls from the housing cooperative complexes than elsewhere in the municipality.

Cooperative Residents Invest in Park Forest

- Many current owners and residents of single-family homes in Park Forest came to the Village as cooperative residents. They found a home because of the lower price for purchasing a share of stock. Over time, their families and personal incomes grew. The positive experience they enjoyed as cooperative residents led them to buy homes in Park Forest. In doing so, they contributed to the sale of more of the Village’s single-family properties.

- Over the years, residents of the housing cooperatives have been extremely civic-minded regarding municipal affairs. A disproportionately large number of housing cooperative residents served on the Village’s volunteer Boards and Commissions. They held public office in the state legislature and on the Village Board as both Mayor and Trustee. They also served on local school boards and have been longstanding local government employees.

What if All Cooperative Complexes in Park Forest Became For-profit?

Consider the potential burden Park Forest would face if somehow the five not-for-profit housing complexes were converted to for-profit. Look at the history of rental complexes in Park Forest and other south suburban municipalities. Consider how many fewer dollars likely would go into building and property maintenance annually. Think how much more costly Village housing inspections and public safety services probably would be. Indeed, consider how much less invested in civic life the more transient rental residents might be. Would the extra taxes generated really compensate for such radical change?

Therefore, a careful consideration of the facts will dispel erroneous notions that Park Forest housing cooperatives burden the local government. Indeed, they may create less tax revenue. However, they also require the expenditure of far, far less public money than many other residential neighborhoods. Meanwhile, they make significant contributions to the well-being of the community at large.

John A. Ostenburg was Mayor of Park Forest from 1999 to 2019. He also served seven years as a Village Trustee and two years as a State Representative. He has been a director of the Birch Street Townhomes Housing Cooperative since 1983 and has been a presenter at several annual meetings of the National Association of Housing Cooperatives.