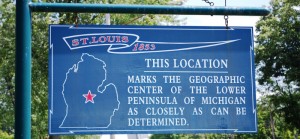

Washington, DC–(ENEWSPF)–June 15, 2015. A community in central Michigan is still dealing with the fallout of a pesticide company that produced DDT nearly half a century ago. St. Louis, MI, a city about one hour north of the state capital Lansing, has long dealt with contamination left behind by the Velsicol Chemical Corporation, which manufactured pesticides in the town until 1963, when it left and abandoned loads of DDT in its wake. DDT, known for accumulating in food webs and persisting for decades in soil and river sediment, was banned in the U.S. in 1972, but problems associated with its prevalent use until that time still plague the community to this day. This situation has led to a multi-million dollar clean-up effort at taxpayers’ expense by Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ).

EPA took control of the Velsicol plant as a Superfund site in 1982, but decades-long delays in the cleanup of the old chemical factory have left songbirds, and potentially people at risk nearly thirty years later. After years of complaints from residents, researchers recently reported that robins and other birds are dropping dead from DDT poisoning. The dead robins and other songbirds tested at Michigan State University had some of the highest levels of DDT ever recorded in wild birds, and it is believed they were contaminated by eating worms in the soil in the neighborhoods around the factory. In 2006, DEQ started sampling some yards in a nine-block area near the plant after complaints from residents. Upon finding DDT in the soil, orange fences were installed around heavily contaminated areas. In 2012, EPA cleaned up those yards, but further sampling found that nearly the entire neighborhood needed remediation.

EPA took control of the Velsicol plant as a Superfund site in 1982, but decades-long delays in the cleanup of the old chemical factory have left songbirds, and potentially people at risk nearly thirty years later. After years of complaints from residents, researchers recently reported that robins and other birds are dropping dead from DDT poisoning. The dead robins and other songbirds tested at Michigan State University had some of the highest levels of DDT ever recorded in wild birds, and it is believed they were contaminated by eating worms in the soil in the neighborhoods around the factory. In 2006, DEQ started sampling some yards in a nine-block area near the plant after complaints from residents. Upon finding DDT in the soil, orange fences were installed around heavily contaminated areas. In 2012, EPA cleaned up those yards, but further sampling found that nearly the entire neighborhood needed remediation.

In 2014, EPA contractors began excavating contaminated soil from 59 yards in the town of 7,000 people, and this summer they will tear up 47 more yards, 10 city-owned properties, the athletic fields at the local high school, and replace St. Louis’ entire water system by tapping into a nearby community’s pipes. Most of the yards are being cleaned because the levels of DDT are a threat to wildlife, however, five of the 47 yards being cleaned this summer have levels of chemicals of concern that exceed human health criteria. One of the yards also has excess polybrominated biphenyls, or PBBs, a flame retardant chemical Velisocol also manufactured and, in 1973, infamously mixed up with a cattle feed supplement, which led to widespread contamination in Michigan. While the majority of the contamination is in the top six inches of the soil, probably from the chemicals drifting over from the plant, some yards have DDT as deep as four feet, according to an EPA report.

DDT is not just toxic to wildlife, but humans too. Researchers have linked DDT exposure to effects on fertility, immunity, hormones and brain development Jonathan Chevrier, Ph.D., an epidemiologist at McGill University, said research suggests that fetuses and young children are most vulnerable to DDT. The major worry is brain development in the womb, he said. “Research shows those with prenatal exposure scored lower on neurodevelopmental scales,” which can indicate lower IQs, he said. There also is evidence that DDT is linked to low birth weights.

In addition to the aforementioned concerns, a study published in July of 2014 found female mice exposed as a fetus were more likely to have diabetes and obesity later in life. This link can span multiple generations, having contributed to obesity three generations down the line from the initial exposure. In another study, lead researcher Michael Skinner, PhD., professor of biological sciences at Washington State University, and colleagues exposed pregnant rats to DDT to determine the long-term impacts to health across generations. The study, Ancestral dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) exposure promotes epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of obesity, finds that the first generation of rats’ offspring developed severe health problems, ranging from kidney disease, prostate disease, and ovary disease, to tumor development. Interestingly, by the third generation more than half of the rats have increased levels of weight gain and fat storage. In other words, the great grandchildren of the exposed rats are much more likely to be obese.

DDT may also induce asthma in St. Louis residents, explains David Carpenter, Ph.D., director of the University at Albany-State University of New York’s School of Public Health and an expert in Superfund cleanups. “Let’s say your backyard has DDT in it. If wind blows, and kicks up dust, you might [be exposed to] DDT. The sun shines, water evaporates, you might get a little DDT,” explains Dr. Carpenter. “And who knows what other chemical exposure they’re getting from the site.”

Nevertheless, EPA officials say St. Louis residents are not in danger, claiming that DDT levels in the soil are not high enough to pose an immediate risk to people. Thomas Alcamo, remedial project manager for the Superfund site, has gone on record stating that, “This [cleanup] is all for long-term risk so there’s no one that needs to leave during cleanup activities.”

Perhaps the most concerning part of this town’s seemingly endless plight is the fact that despite wildlife deaths and some lawns contaminated to levels deemed harmful to humans, no one is conducting health testing on DDT exposure in the community. Mr. Alcamo said a comprehensive health study of the community would be the responsibility of the state’s health department or the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, neither of which is studying the community. The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services spokeswoman recently stated that the department “is neither planning or currently conducting a human health study or an exposure investigation in that community.”

Failure to look into the human health effects that could be plaguing this community more than four decades after the ban of DDT is not only an unjust act towards community members that may be suffering from adverse health effects, but it is also a disservice to the greater American public. The fact that the EPA has only just begun to scratch the surface, both literally and figuratively, when it comes to addressing some of the long standing effects of a once widely used pesticide should serve as a warning and speak to the dangers of using pesticides when long-term environmental and health effects are unknown. Stories like this one from St. Louis, MI should make us heed warning of short term health effects and be wary of long term exposures.

In light of recent discoveries, like the classification of glyphosate as a human carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), or the environmental effects caused to bee populations by neonicotinoids, a persistent chemical that may be a bigger threat than DDT, local governments, states and the EPA should learn from the past and work together to try and prevent the kind of long-term damage being experienced by the residents of St. Louis, MI and other communities around the country.

Sources: Environmental Health News, www.beyondpesticides.org

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.