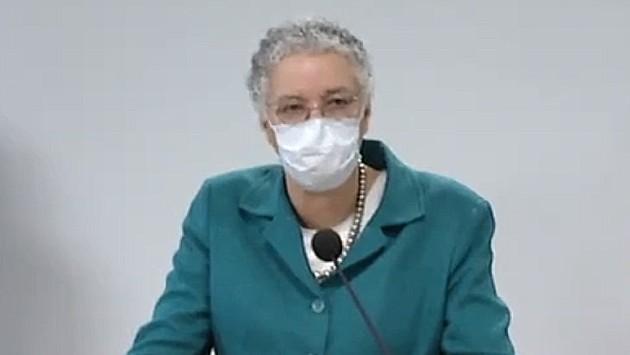

Chicago, IL-(ENEWSPF)- Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle issued a statement praising the decision of Judge Anna Demacopoulus to not release the names of patients who test positive for COVID-19 in Cook County.

“Today, Judge Demacopoulos denied the Northwest Central Dispatch Systems emergency request to release the names and addresses of COVID-19 positive patients in suburban Cook County,” President Preckwinkle said in a statement.

“Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, we are deeply grateful to the dedication and bravery of our first responders. However, I remain supportive of the Cook County Department of Public Health’s decision not to release such information in order to preserve the private health information of Cook County residents.

In order to maintain patient privacy while also prioritizing our first responders’ needs for information and personal protective equipment, Cook County will continue to encourage the use of CCDPH’s ShinyApp which displays COVID-19 data for suburban Cook County under the jurisdiction of CCDPH; encourage Cook County residents to utilize the Smart911 technology, and continue to work with our municipal and first responder partners to continue to secure additional PPE through our local, state and federal resources,” President Preckwinkle said.

First responders, generally, are sworn officers or officials in Cook County. As such, the 1964 Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) Case New York Times v. Sullivan applies to these officers, as well as elected and appointed officials.

The SCOTUS case essentially concludes that public officials are public property. That may seem like a stretch, but that’s the substance of the decision. So, much information about such officials, officers, etc., is subject to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, including, but not limited to, their salaries, for example.

Judge Demacopoulos’ decision puts the health status of appointed and elected officials out-of-bounds, as it should. We applaud the decision of Judge Demacopoulos and hope that it stands up if appealed.

What was involved in The New York Times Co. v. Sullivan? Anyone considering a run for public office or appointed office of any kind should read it before circulating peititions. Here’s the basic issue, directly from the decision, written by Supreme Court Justice William J. Brennan, Jr.

Respondent, an elected official in Montgomery, Alabama, brought suit in a state court alleging that he had been libeled by an advertisement in corporate petitioner’s newspaper, the text of which appeared over the names of the four individual petitioners and many others. The advertisement included statements, some of which were false, about police action allegedly directed against students who participated in a civil rights demonstration and against a leader of the civil rights movement; respondent claimed the statements referred to him because his duties included supervision of the police department.

L. B. Sullivan was one of the three elected Commissioners of the City of Montgomery, Alabama. He brought civil action against four black Alabama clergymen and the New York Times. A jury in the Circuit Court of Montgomery County awarded him damages of $500,000, the full amount claimed, against all the petitioners, and the Supreme Court of Alabama affirmed. Sullivan claimed that he had been libeled by statements in a full-page advertisement that was carried in the New York Times on March 29, 1960. Entitled “Heed Their Rising Voices,” the advertisment stated the following:

“As the whole world knows by now, thousands of Southern Negro students are engaged in widespread nonviolent demonstrations in positive affirmation of the right to live in human dignity as guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights.”

It went on to charge that,

“in their efforts to uphold these guarantees, they are being met by an unprecedented wave of terror by those who would deny and negate that document which the whole world looks upon as setting the pattern for modern freedom. . . .”

Succeeding paragraphs purported to illustrate the “wave of terror” by describing certain alleged events. The text concluded with an appeal for funds for three purposes: support of the student movement, “the struggle for the right to vote,” and the legal defense of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., leader of the movement, against a perjury indictment then pending in Montgomery.

The third and sixth paragraphs of the ad were Sullivan’s libel complaint:

Third paragraph:

“In Montgomery, Alabama, after students sang ‘My Country, ‘Tis of Thee’ on the State Capitol steps, their leaders were expelled from school, and truckloads of police armed with shotguns and tear-gas ringed the Alabama State College Campus. When the entire student body protested to state authorities by refusing to reregister, their dining hall was padlocked in an attempt to starve them into submission.”

Sixth paragraph:

“Again and again, the Southern violators have answered Dr. King’s peaceful protests with intimidation and violence. They have bombed his home, almost killing his wife and child. They have assaulted his person. They have arrested him seven times — for ‘speeding,’ ‘loitering’ and similar ‘offenses.’ And now they have charged him with ‘perjury’ — a felony under which they could imprison him for ten years. . . .”

You could argue that Sullivan was already on thin ice with this suit. His name never appears in the advertisement. Sullivan disagreed:

Although neither of these statements mentions respondent by name, he contended that the word “police” in the third paragraph referred to him as the Montgomery Commissioner who supervised the Police Department, so that he was being accused of “ringing” the campus with police. He further claimed that the paragraph would be read as imputing to the police, and hence to him, the padlocking of the dining hall in order to starve the students into submission. As to the sixth paragraph, he contended that, since arrests are ordinarily made by the police, the statement “They have arrested [Dr. King] seven times” would be read as referring to him; he further contended that the “They” who did the arresting would be equated with the “They” who committed the other described acts and with the “Southern violators.” Thus, he argued, the paragraph would be read as accusing the Montgomery police, and hence him, of answering Dr. King’s protests with “intimidation and violence,” bombing his home, assaulting his person, and charging him with perjury. Respondent and six other Montgomery residents testified that they read some or all of the statements as referring to him in his capacity as Commissioner.

The Supreme Court rejected Sullivan’s arguments, holding “A State cannot, under the First and Fourteenth Amendments, award damages to a public official for defamatory falsehood relating to his official conduct unless he proves ‘actual malice’ — that the statement was made with knowledge of its falsity or with reckless disregard of whether it was true or false. “

The key here is “actual malice.” Was there actual malice involved? SCOTUS said no, and this decision has been the standard-bearer for all cases that followed.

In short, to paraphrase a former colleague of mine, you would have to falsely accuse a public official of something absolutely horrible, like infanticide, say that you know it is true, that you have seen proof — all the while knowing that what you are saying is a damn lie. Like it or not, public officials are considered “public property,” and the public can say almost anything at all about them, true or false, and face no consequence for doing so.

From SCOTUS again:

In Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 U. S. 250, the Court sustained an Illinois criminal libel statute as applied to a publication held to be both defamatory of a racial group and “liable to cause violence and disorder.” But the Court was careful to note that it “retains and exercises authority to nullify action which encroaches on freedom of utterance under the guise of punishing libel”; for “public men are, as it were, public property,” and “discussion cannot be denied, and the right, as well as the duty, of criticism must not be stifled.”

In essence, your main limitation on what you can and cannot say about a public official is your conscience. The law will let you say a lot.

Did you ever wonder why some politicians running for office say the most awful things about their opponents and get away with it? Despicable and lowly as this behavior is, it’s because they can. If you don’t like their behavior — and you shouldn’t — then campaign against them.

Again, from SCOTUS:

We reverse the judgment. We hold that the rule of law applied by the Alabama courts is constitutionally deficient for failure to provide the safeguards for freedom of speech and of the press that are required by the First and Fourteenth Amendments in a libel action brought by a public official against critics of his official conduct.