EU–(ENEWSPF)–12 September 2011.

|

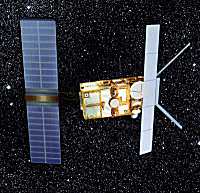

ERS-2

|

After a final thruster firing last week to deplete its remaining fuel, ESA’s venerable ERS-2 observation satellite has been safely taken out of service. Ground controllers also ensured the space environment was protected for future missions.

The mission ended on 5 September, after the satellite’s average altitude had already been lowered from 785 km to about 573 km. At this height, the risk of collision with other satellites or space debris is greatly reduced.

The final critical step was to ‘passivate’ ERS-2, ensuring that all batteries and pressurised systems were emptied or rendered safe in order to avoid any future explosion that could create new space debris.

This primarily consisted of burning off the fuel, disconnecting the batteries and switching off the transmitters.

“As soon as we saw fuel depletion occurring, a series of commands was sent to complete passivation, before shutting the satellite down for good. The last command was sent at 13:16 GMT on 5 September,” said Frank Diekmann, ERS-2 Operations Manager.

|

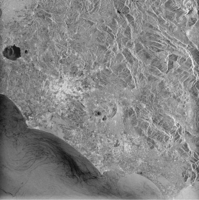

Final ERS-2 image showing Rome, Italy

|

Valuable data archive

The end of flight operations does not mean the end of the mission’s usefulness, though.

“We will continue exploiting data gathered by ERS-2, especially the radar imagery,” said Volker Liebig, ESA’s Director for Earth Observation Programmes.

“Combining this rich scientific store with new data delivered by improved radar instruments on the GMES Sentinel-1 mission will generate strong synergies as we work to understand our planet’s climate.”

Atmospheric burn up

With the effects of natural atmospheric drag, ERS-2 is predicted to enter and largely burn up in the atmosphere in about 15 years. This is well within the 25-year-limit that is imposed to minimise the risk of collision before re-entry.

“ERS-2 deorbiting is being conducted in compliance with ESA’s space debris mitigation requirements,” said Heiner Klinkrad, Head of ESA’s Space Debris Office.

“This indicates the strong commitment by the Agency to reducing space debris, which can threaten current and future robotic and human missions.”

|

Part of the ESA team at ESOC for deorbiting

|

End of 16-year mission

ERS-2 was launched in 1995, four years after ERS-1, the first European Remote Sensing satellite. The missions paved the way for the development of many new Earth observation techniques.

“ERS-1 and -2 delivered 20 years of continuous high-quality data covering the oceans, land, ice and atmosphere,” said Wolfgang Lengert, ERS-2 Mission Manager.

“Throughout these two decades, the emphasis has been on quantifying measurement accuracy and documenting results, ensuring the data will serve as a heritage for future generations.”

ERS-2 travelled 3.5 billion km during its lifetime, providing data for thousands of scientists and projects.

|

Some of Operations team discussing deorbiting procedures

|

Operations team prepares for deorbiting

Mission controllers, flight dynamics specialists and technical experts prepared for many months prior to starting the deorbit procedure in July 2011.

Lowering the satellite’s orbit to 573 km came after a set of 66 carefully controlled manoeuvres commanded by the mission control team at ESA’s European Space Operations Centre (ESOC) in Germany during July and August 2011.

“At this targeted altitude, the satellite orbits Earth exactly 15 times a day, and we could monitor ERS-2 shut-down activities via a chain of ground stations,” says Xavier Marc, the mission’s lead flight dynamics engineer.

“Now, its orbit will slowly decay due to natural atmospheric drag.”

Three of ERS-2’s six gyroscopes failed in the early years of the mission, and the data storage system ceased functioning in 2003, making deorbiting a particular challenge for the ESOC team.

Depleting fuel avoids creating future debris

On 26 August, controllers began the last series of thruster firings that alternately raised then lowered the spacecraft altitude, using up substantially all remaining fuel. The firings took place several times per week, running up to 40 minutes each.

The firings occurred during mid-afternoon while the satellite was nearly continuously tracked by the Agency’s 15 m ground stations in Kiruna (Sweden), Maspalomas (Canary Islands) and Kourou (French Guiana).

Additional tracking support was provided by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency station at Katsuura, near Tokyo, and the Svalbard station in Norway, operated by KSAT.

|

Mission complete: ERS-2 deorbiting team at ESOC

|

Keeping an eye on the gas

“The orbit and the selected ground stations offered a nearly uninterrupted spacecraft visibility slot of approximately 50 minutes each day where fuel depletion could be conducted and closely monitored,” said Marc.

“The challenge was to burn up as much fuel as possible right up until it was substantially all gone, then quickly shut down the satellite’s subsystems while we were still tracking it in ground station visibility.”

Unlike a car, ERS-2 had no convenient fuel gauge showing when it was, say, nine-tenths empty. Instead, engineers had to monitor a set of parameters carefully that indicated thruster activity and the fuel system’s pressure and temperature, and use these to estimate the mass of remaining fuel.

Controllers could also monitor parameters that indicated when thrust had become uneven or intermittent, which also showed whether fuel had been depleted.

In recent days, Diekmann and the ESOC team monitored each depletion firing minute-by-minute from the mission’s Dedicated Control Room, watching intently for the signs that fuel was nearing exhaustion.

“ERS-2 deorbiting demonstrates excellent team work at ESA, directly fed by the unique expertise gained by the flight dynamics and flight control teams at ESOC during 20 years of demanding ground control for ESA Earth observation missions, including ERS-1 and ERS-2,” said Manfred Warhaut, ESA’s Head of Mission Operations.

Source: esa.int