Commentary

By Gary Kopycinski

BLOG COMMENTARY-(ENEWSPF)- All of us, regardless of our race, gender or ethnicity, need to talk about racism in America. We need to talk about owning racism. The only wrong way to talk about racism in America is to not discuss it.

Perhaps.

The only way to learn how to talk about racism in America is to talk about racism in America.

So permit me to join the conversation.

Let me begin by suggesting a distinction between “racism” and “acting in a racist manner” or “saying something that is racist.”

There is a difference.

We have all heard people make ugly comments at one time or another in our lives. When one person hurls an insult at another person, and that comment is directed at someone because of his or her race, then the person who made the comment is acting in a racist manner.

Racism is much uglier, and it is endemic in American society. America was formed with racism as a priority from the start.

That is an ugly truth we must own and accept.

Racism = Prejudice + Power

A classic and still-emerging definition of racism is this: Racism = Prejudice + Power (See Kinder and Sears, then here and here too). We all have our prejudices, and we spend a lifetime working to overcome them. As a Catholic, my church asks me to spend time during the current liturgical season of Lent to examine my own attitudes, determine where I need to grow to be a better person, to work to treat all people in a loving manner. And I will spend my life learning to do that in a better way.

Racism, however, goes beyond prejudice. Racism happens in a society when a group of people have the power to put their prejudices into law and/or policy, and they do so. That society becomes ordered according to these prejudices, and that happened here in America, and those prejudices are still deeply, deeply ingrained in our society, the corporate world, and, yes, in our government.

Consider the following: the writers of the Declaration of Independence had a bit of a dilemma. Yes, they had it with the British, but how were these very wealthy white men going to convince people in the rest of the colonies to go along with their cries for revolution? Howard Zinn writes about this quandary in A People’s History of the United States. The writers had to sell the idea of a revolution to the many, many poor who would be called on to fight, and, in many cases, give the ultimate sacrifice.

So they spoke about ideals. How will this new country be different when independent as opposed to remaining under British rule?

They created a dream, the American Dream:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

Many Americans know the first line of this paragraph by heart, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

“Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

That was 1776. In the 1791 Bill of Rights, that phrase enters the constitution through Amendment 5, but with a twist:

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

“Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,” becomes “life, liberty, or property.”

The phrase surfaces again in Section I of the 14th Amendment:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

“Happiness” is sadly absent from the constitution. In its place, “property.”

What does this have to do with racism? When the original Constitution of the United States was written, the promises applied only to white men. People of Color were excluded. White men who did not own property or enough property were also initially excluded.

African Americans and women of any color, of course, were completely shut out, excluded.

Racism Means Denial of Opportunity

The above is only a snapshot, of course. Before the Declaration of Independence, centuries of slavery had already made racism, exclusion of certain groups, a legal and official part of this country. And it stuck. Our own, 100% American, deeply entrenched institutionalized racism.

“But can’t anybody get a job who wants one?” I will hear people say today. “After all, this is the land of opportunity. All that was centuries ago.”

Would that it were that simple.

Many in powerpoint fingers at the poor. We see this ugliness all the time played out again and again in the political world.

Can anyone get a job who wants one? Or do money and a good education help? Do all have the same opportunities? Does the young person growing up in Ford Heights have the same shot at getting into an Ivy League school as a young person growing up in Naperville?

Aren’t we supposed to pick ourselves up by our bootstraps, whatever they are?

The facts say otherwise. Exclusion of certain classes of people, largely based on race and wealth, was the American way for centuries. Many fought to overcome these obstacles for so many.

Have you wondered why there is no looting in Japan? Much of it has to do with Japan’s largely robust economy after World War II, where a large percentage of the population was brought into the middle class.

A sense of order, moreover, is not confined just to government manuals. In the wake of the disaster, there has been no looting, no rioting. Even as people hoping for food, water and fuel wait in kilometer-long lines in freezing weather — sometimes without success — tempers have not flared. Rationing of basic supplies has been accepted with few complaints. The assumption is that everybody has to share the pain equally. At Masuda Middle School, one of hundreds of emergency centers housing some 450,000 homeless people, the loudspeaker emitted a crescendo of friendly announcements. “Please come enjoy your piping hot rice now,” went one. “Please be alert to the fact that the fish roe is a bit spicy, so it may not be suitable for small children,” went another. In the emergency shelter at Koizumi Middle School, people not used to wearing shoes indoors constructed origami boxes made of newspaper in which to nestle their footwear.

And again from the same article:

Still, the elderly who survived the March 11 catastrophe know better than any other Japanese how quickly their homeland can revive itself. My grandmother used to recall the U.S. firebombing of Tokyo during World War II, which reduced half the capital to rubble. The pictures of that era bear a haunting resemblance to the images coming out of northeastern Japan today. Yet within two generations, Japan had transformed itself from a defeated land into the world’s second largest economy. Incomes were spread relatively equally, with little poverty to speak of. Japan took on a contented, comfortable air.

Perhaps too much so. For while there are lessons to be learned by other nations from both Japan’s postwar success and its resilience in the face of disaster, rigid hewing to the rules and the suppression of individual creativity for the common good can go too far. They may, indeed, have undermined Japan’s economic miracle. (Just try to order a salad with the dressing on the side in Japan and watch the consternation of the waiter at such an unorthodox request.) After the bubble economy of the 1980s collapsed in 1991, Japan entered a long economic slumber, from which it has yet to fully wake. Last year, China surpassed Japan to take the spot as the world’s No. 2 economy.

America has a different story to tell. Many times, when Americans riot, these riots take place in neighborhoods where many still live who have historically been denied opportunity. And the media pounces, quick to show us “those people” rioting, making sure we see the color of their skin. Then, some of our less-enlightened citizens watching on television look at each other with knowing glances, happy that their prejudices have been affirmed again.

Racism is part of the American psyche. In corporate America, how many CEOs are persons of color? For centuries, people of color were denied opportunity, with no chance to get in the front door, let alone make their way to the board room.

We must have this conversation. People are still being excluded, even while the wealth in this country flows fast to the top.

“Life, liberty, and property.”

“Life, liberty, and stay away from my stuff.”

How Park Foresters Decided To Be Different

I just did a double-take. I was going to call this concluding section, “How Park Forest Is Different.” I decided, however, that it’s not about the town, it’s about the people.

A generation-and-a-half ago, Park Foresters decided to be different, and that has made all the difference for those of us living here today, as well as the rest of the South Suburbs.

After he marched in Chicago, after crowds of angry whites threw stones at him as he led a march in the Gage Park section of Chicago’s southwest side, Martin Luther King, Jr. told journalists he had never encountered such hostility, not even in the deep South.

In the mid- to late-50s, Park Foresters decided they did not want to be Chicago. They wanted to be different, and they began to actively recruit People of Color to move into town.

From the Park Forest Historical Society’s Web page:

The village was integrated, peacefully, in December 1959. This happened at a time when other suburbs across the country, including the Levvittowns, were experiencing serious acts of discrimination against their first African American residents. The Social Action Committee of the Unitarian Church helped bring the first African American, Dr. Charles Z. Wilson, and his family to Park Forest. The Human Relations Commission joined the SAC in going into the neighborhoods to ease the way of each African American family for many years after that. Later, Park Forest instituted a program of Integration Maintenance to avoid block-busting and white flight, successfully maintaining a well-balanced, integrated village.

Park Forest has been studied for integration, sociology, city planning and the history of suburbia in the mid-20th century. William H. Whyte’s book, The Organization Man, published in 1956, was researched here. Gregory Randall published, America’s Original GI Town in 2000. Both books are used as textbooks around the world. Jerry Shnay wrote Park Forest Dreams and Challenges for Arcadia Publishing. It sells around the world, and you can buy it in the museum.

It wasn’t all a bed of roses, of course. In his 1967 article Negro in the Suburbs, senior editor of Look magazine Jack Star notes that some newcomers to Park Forest were greeted in less-than-friendly ways, but those instances seem to have been rare.

Dr. Wilson’s three-year stay in Park Forest was “uneventful,” Star writes. Dr. Wilson moved out to take a teaching job elsewhere.

‘Being a Negro in the middle of white people is like being alone in the middle of a crowd,’ says Mrs. Jacqueline Robbins, a young Negro housewife who lives in the Chicago suburb of Park Forest, Ill. In December, 1962, Mrs. Robbins, her chemist husband Terry, 32, and their two sons moved into the then all-white suburb, whose first, and only Negro family had just recently moved out…The Robbins are not alone. Although Negroes are still a rarity in the green reaches of suburbia, they are emerging from nearly all the large metropolitan ghettos with increasing frequency. In Chicago last year, 179 Negro families moved into white suburbs-more than twice as many as in the previous year, seven times as many as in 1963, and 45 times as many as in 1961 and 1962 combined.

“The only really unpleasant experiences,” Star writes, “are reported by a Negro couple who say their next-door neighbors were hostile. One neighbor put up an eight-foot fence; the other hung a blackface doll in his window. ‘The lady with the fence walks out the minute my wife shows up at a PGA meeting,’ says the husband. ‘And the name-calling is something terrific. It’s hard on the kids.”

In one instance, another man ordered his landlord to put up a fence between the properties when he heard a black couple was moving in. The landlord did, and the man painted his side of the fence white, the other side black, Star writes. An officer from the Park Forest Police Department volunteered to paint the black side of the fence white for the new neighbors.

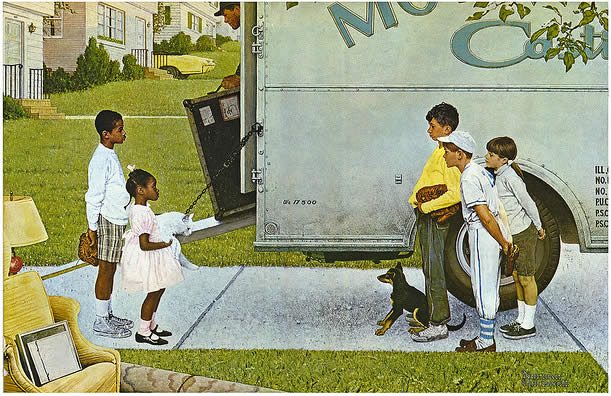

Legendary artist Norman Rockwell took note also, creating in 1967 the painting at the top of this article, Moving In.

From the Norman Rockwell Museum:

At 73, Rockwell had lost the energy to develop his work in the painstaking way of the previous half-century. Now he would often omit the intermediary step of preparing a detailed charcoal drawing before proceeding to paint in oil. In addition, his color perception was diminishing due to cataracts. Still, his work continued to reach an appreciative audience.

In his illustration of suburban integration in Chicago’s Park Forest community, Rockwell was secure in expressing his philosophy of tolerance. We can see the children will soon be playing with each other, but the face peering from behind a window curtain makes us wonder how the adults will fare.

Park Foresters long ago decided they wanted to be different. They wanted every white child to know and hopefully become friends with a black child. They wanted a peacefully-integrated community, and they worked hard to achieve that dream.

The ideal these Park Foresters began to strive for a generation-and-a-half ago is this: Park Forest is not the place you left. Park Forest is where you belong, regardless of who you are.

Our discussion on racism in America, about owning racism, must continue. I have much to learn still, as do we all. Please forgive this clumsy beginning.

Collectively, we must continue to unravel the racism still entrenched in our society, where many are still denied opportunity while others grasp so firmly their wealth.

As we study our failures, however, we must learn from our successes as well. Park Forest is part of that success, and a lesson for America, and Americans everywhere.